2 Elementary School

2.1 Pre-memories

My mother was already three months pregnant with me during the Cuban Missile of October 1962. She tells me that week she stocked up on as much food as she could, hoping to stock enough to care for my older brother, who himself was only six months old.

The crisis had passed by the time I was born the following April, but by then she was too overwhelmed to care. She gave birth to me at the Neillsville Memorial Hospital during a record-setting heat wave. In the days before air conditioning, she would not have been very comfortable, but she was young, a 22-year-old farm girl toughened up by cold Wisconsin winters.

She brought me home to a small apartment in the nearby town of Granton, where my father had found work as a math teacher. Having just turned 23 himself, he was only a year out of the Eau Claire State Teachers College where they had met. Most of their classmates were already married and out in the world just like they were. In those days it just seemed like the normal thing to do upon turning 18: get married, have kids, settle down.

It’s hard to tell, after more than fifty years, which of my own memories are genuine and which are “memories of memories”, the foggy chimeras inherited from long-forgotten discussions about my earliest memories. Nevertheless there are a few incidents I can recall with enough clarity, and that fit the basic facts, well enough that I think they qualify.

My brother Gary was barely ten months older than me, and my sister Connie was only a year younger, so they were in all of my memories. I vaguely remember playing with them, on a hard wooden floor – maybe at Grandma’s house? All of my early memories are happy and content.

I remember living in a house in Eau Claire1, with back yard facing into a woods. It was Autumn, or perhaps Spring, because there were dead leaves on the ground, without much vegetation. There was a dog – I don’t think it was our dog – and he was running into the woods, so I followed. After a short distance, I noticed I was getting far from home so I stopped, hoping the dog would return, but he never did. That’s the memory: that’s it. The rest is an unsatisfying lack of closure, wondering what happened.

My parents tell me that we didn’t have a dog at the time, so it must have been a neighborhood pet. But what was it doing in our yard? Why did it leave such an impression on me? Who knows?

I vaguely remember the house itself: yellowish paint on the inside, a front door that opened directly into the main room, facing the tiny kitchen. A sofa to the left of the door blocked off the living room, where a child’s crib (my sister’s?) had been set up. Later my parents told me a story how, upon bringing my baby sister home from the hospital and setting her in that crib, my brother and I felt the urge to make her feel at home. We donated our favorite toys (or so the story goes), some heavy steel-made Tonka trucks, which we somehow tossed into the crib, barely missing the poor baby.

Another memory, set in the same house: I was talking with my mother, apparently about an upcoming birthday. “Your birthdays keep rolling along,” she said, and in my mind I pictured a birthday cake, spinning up the hill to our house. If that memory is accurate, based on the dates that my family was living in that house, it would have been just before my third birthday.

My left wrist bears a very light scar, nearly faded after half a century, which my mother said is the aftermath of an injury involving a toy drum set. I have no memory of this at all, but in my mind’s eye I picture a cheap, exposed metal ring protruding from a plastic covering, somehow digging into my wrist. It must have been more traumatic for my mother than for me, because if there were any long-term effects, I soon forgot them.

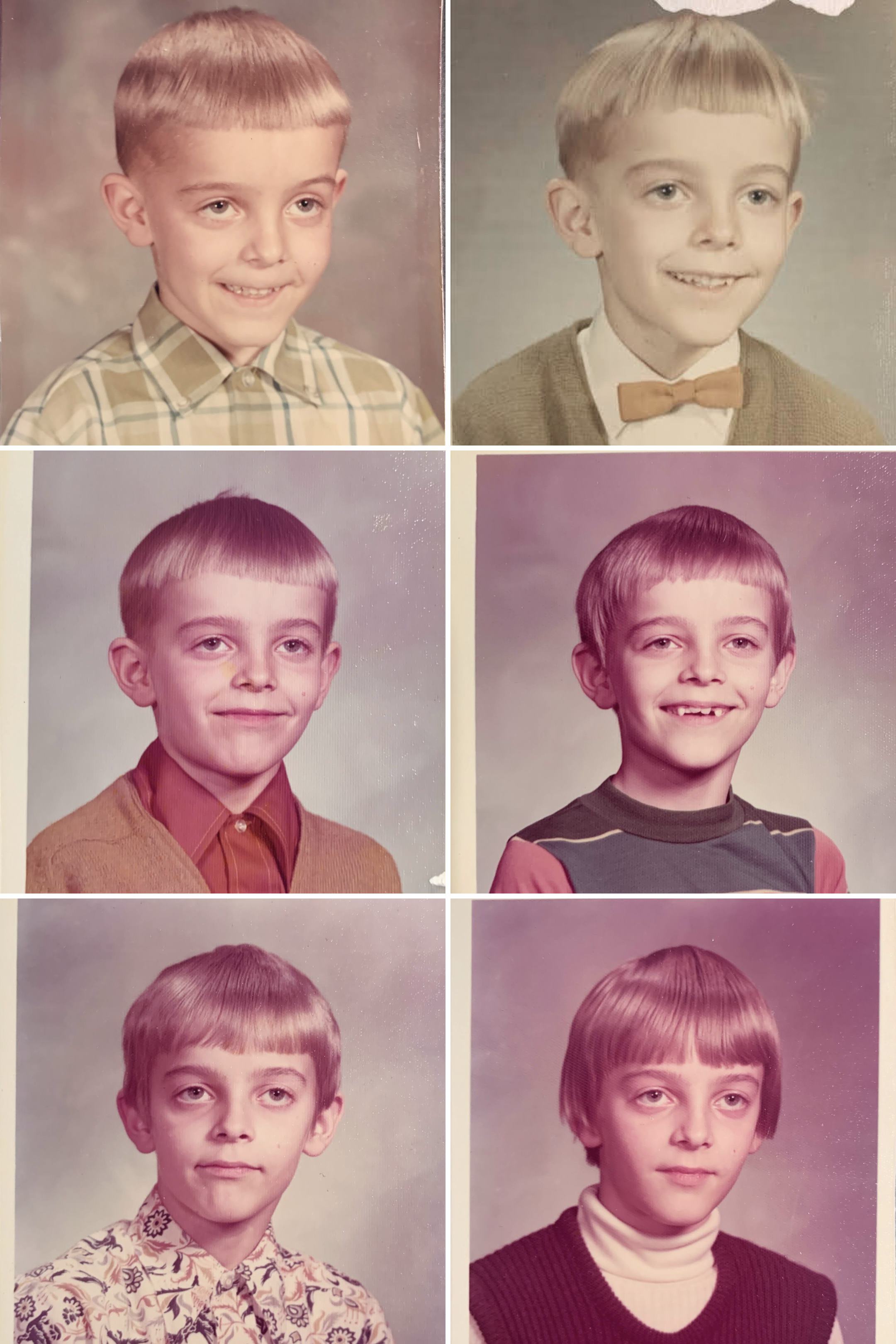

For years during my childhood, my mother called me by the nickname “mouse”, because she says I was so silent as I crawled through the house. If I was unusually quiet for a small boy, it may have simply reflected my overall sense of contentment. In photos, the baby me was always smiling, looking contentedly at the camera (no doubt, happy to oblige the requests of whoever was taking the picture).

We moved to Neillsville by the time I was four years old, most likely in the summer, in time for my father to take a job as a science teacher at the high school. Our first stop upon arrival was at our new church, the Neillsville Assembly of God, and there I made my first friend: Tommy Mohr, whose mother was the church secretary2. His older brother Bobby became my brother’s friend. Though I remember little else about the Novak boys from those earliest days, I imagine we saw them regularly – several times a week – before and after church services, no doubt and perhaps in between. They lived in the country, so it would have been impractical to visit him at his house – my memories of our rare visits there are when he was a bit older.3.

That’s it. Those are my only memories of life before elementary school. I would have begun with kindergarten, after I had turned five in April of 1968, so an entire year had passed in Neillsville before my memories kick in. That seems odd, now that I think about it – a move to a new city spurs no special memories in a child of that age – but perhaps I was so content, so trusting of my parents, that the surroundings of home and neighborhood just faded into the background. I was a happy baby, living a contented early childhood with a family who loved me, and maybe that’s all I need to remember.

2.2 Elementary Stories

My first day of kindergarten was a disappointment. Our teacher, a white-haired woman named Mrs. Helen Smith, was by the time I joined her class in the 1960s had no doubt been teaching since before World War II, and I’m sure nothing about a group of five-year-olds was unfamiliar. When our classmate Jane, who could not bear to be parted from her mother for the few hours in the afternoon for our half-day classes, began the class with sobs and whimpers, Mrs. Smith promptly dispatched her to the art closet, ensuring the rest of us would be undisturbed by her distress. When, sometime during the year, my classmate Doug swallowed some pennies, she knew to calmly call the Principal, who drove him to the hospital.

My brother, who had his first day a year previous and who, as far as I was concerned had demonstrably achieved greatness in all things Kindergarten-related, proved to me that school was a busy, happy place, full of art projects and alphabet practice – and familiar playmates. I didn’t know the children surrounding me on that first day, but I would. Most of them would be my companions for the next twelve years, and more than half would remain known to me for the rest of my life. Of the hundred or so kindergarten kids, split into four classes – two in the morning, two in the afternoon – perhaps seventy-five or eighty would be together at high school graduation. Thirty years after that, about forty would gather for our class reunion, many of them with grandchildren already attending the very same school.

Mrs. Smith promised us that our first day would be an easy one: some play time, a song or two, a brief introduction to the fun we’d have during the year, a snack, and – if we had time, she assured us—a nap. The rest of the agenda happened as promised, but the nap never materialized and I went home with the cocky self-confidence of a five-year-old who knew already that sometimes teachers are wrong.

Never mind, soon I was caught up in the daily rituals of school. In those days, none of us entered kindergarten with any experience with the alphabet, or with numbers, so there was plenty to learn.

The best part of school was the toys: trucks, wooden bricks, and guns for the boys; a pretend kitchen complete with pots and pans and fake plastic wigs for the girls. I don’t remember recesses outside. Maybe we didn’t have any: in the cold Wisconsin winters it would have been a big project for Mrs. Smith to dress up all those kids, send them outside, and reverse the process when they came back in. No matter: I wasn’t much of an outdoors type, and playing with balls or other sports wouldn’t have appealed to me. I preferred to play in that pretend kitchen, with the girls, though eventually Mrs. Smith corrected me and made clear that I needed to be with the boys. Oh well, that was okay too.

2.3 Charlie Brown

I remember little about the circumstances that led our parents to drive us to a farm outside Neillsville where we were greeted with our new puppy, who for some reason we promptly named Charlie Brown.

“Chucky”, as we often called him, was a part-chihuahua, part-terrier mixed breed descendent of some indoor farm dogs. More important than the breed, though, was the purpose of the dog. In rural communities like ours, dogs were divided into two categories: farm dogs – which lived outside – and indoor dogs, where were kept strictly as pets.

Farm dogs were large and given free roam to mingle and travel however they liked. Good farm dogs helped round up the cows or other stray animals, scared off any deer or other intruders that attempted to graze on a vegetable garden, and generally provided overall security services. It didn’t matter the farm – if you for some reason attempted to sneak into a neighbor’s yard at any hour of the day or night, you were guaranteed to be greeted by the loud bark of a farm dog.

Farm dogs lived outdoors year round, sheltered in a small dog house built for them. On the coldest of winter nights they might be given access to the barn, but generally the breeds that thrived in Central Wisconsin were the type that if anything preferred the cooler weather of the winter. Huskies, Collies, Danes – large animals with hearty appetites and friendly, curious personalities that kept watch over the farmstead.

By contrast, an indoor dog like Charlie Brown was suitable mostly as a pet, like a loving sibling whose only responsibility was to provide affection to the other family members. Ostensibly tasked with home security services like their outdoor cousins, most of these pets were pretty worthless. Charlie Brown was happy to bark at intruders when circumstances were obviously peaceful, but he wouldn’t hesitate to hide under the bed if he thought there was any real danger.

We once tried to breed him – we lent him for a weekend to a family whose female dog was in heat – but Charlie showed no interest. He could be a little touchy around other dogs, and occasionally would nip at a stranger if provoked. He slept a lot.

Still, he was our dog and we treated him like family. He ate when we ate (including table scraps), and often accompanied us when we were outside playing. I don’t remember having any specific duty to take him on daily walks – I assume my mother did that, or perhaps the only “duty” was to open the door and let him come back when he was finished.

I don’t remember ever asking neighbors or others to watch him when we were out of town. Charlie came with us everywhere. After all, he was part of the family.

2.4 Hospital

A few months after Kindergarten, my teacher called my mother to pick me up early. I’d been experiencing such a severe stomach ache that even a hardened teacher like Mrs. Smith knew it was hopeless to expect me to finish the half-day class. At first my parents assumed that it was something I ate, or that I’d eaten too much, but when the pain continued the next morning, they thought maybe I’d caught a virus of some sort and kept me home from school. I was feverish and couldn’t hold down food, and after a few more days they became concerned.

My family didn’t have a lot of income, but in those days it wasn’t unusual to be like us without health insurance of any kind. Doctor visits were cheap, especially for routine things like childhood vaccinations, so most people just paid for their medical bills in cash. But even the few dollars it would cost to visit the Neillsville Clinic was a tradeoff for my parents – it was money that couldn’t be spent on other things – so I was kept home in my mother’s care until finally they decided that my condition wasn’t a normal illness. They needed professional help.

I don’t remember much about my first visit to the hospital. My mother knew Dr. Thompson, the doctor who had delivered me five years previously, but this time I was assigned to Dr. Ozturk, one of two Turkish-born doctors of the four or five doctors at the Neillsville Community Hospital. He spoke with a friendly accent, his face smiling and eyes squinting when he examined me.

He was a surgeon. The small staff at the hospital had determined that I had a bowel obstruction – my intestines were wrapped around themselves in a tight knot that prevented passage – and having waited so long for treatment, I was in a dangerous situation.

Bowel obstructions are very rare in small children. Years later I learned that, as a baby, I was born with a hernia, a not uncommon condition caused when the navel doesn’t completely close over after the umbilical cord is cut.4 In nearly all cases, the belly button closes over naturally in a few weeks or months, but in my case it took longer – years – and apparently a piece of my bowels had become entangled as a result, leaving me obstructed.

The standard treatment is to wait it out, inserting a tube through the nose into the stomach to release pressure on the intestines. An intravenous (IV) drip was placed into my tiny five-year-old arm to give me some badly-needed hydration and food. But I had already waited too long, and my condition remained serious. This would not resolve itself on it’s own, Dr. Ozturk concluded, and arranged for surgery.

Operating on a five-year-old is a big deal to any parent or relative, but I don’t remember much. In later hospitalizations I would revel in the attention, but perhaps my condition was so serious that I was simply too weak to notice anything.

They operated, and along the way Dr. Ozturk decided to remove my appendix. I’m unsure why. Appendicitis is very unusual – perhaps unheard of – at that age, and it would have been a straightforward procedure to adjust the bowels to end the obstruction. Maybe my condition was worse than expected, and inflammation had spread to the appendix? More likely, I now think, he removed the appendix because to a 1960s doctor, it was a vestigial organ whose only effect on health would be negative, if later inflamed, and he thought that as long as he was in there anyway, he might as well get rid of it and save any potential later trouble.

Anyway, the surgery was a complete success and I made a full recovery. I was back in kindergarten, back playing with my friends, back with my family, just a normal five-year-old boy. The only change was that now I had a story, something that made me special. I was the kid in the family who’d been in the hospital.

2.5 More Hospital

After kindergarten, after my appendix had been removed, I seemed to have fully recovered, yet I continued to have stomach pains, which my mother treated with Pepto Bismol. The raw pink taste of the gallons I drank still hasn’t faded after all these years, but at the time my situation didn’t seem particularly disturbing. After all, I was a small boy who’d just had major surgery. Otherwise I continued to develop normally and all seemed fine.

But sometime in third grade, my situation became much worse. The doctors wrote the following notes on August 14, 1971:

The child had been sick for about a year and probably more. He would chronic abdominal pain and off and on his breathing was not regular. There was something wrong going on in his abdomen and the parents did not have any insurance, his father is a minister and does not have much money and he did not bring the child for exam. On admission he was chronically ill and he was in a mal-nutritive state. He was slightly toxic and his growth was a little below the average. For the past three or four months the child would not eat because he stated to his parents that his abdomen gets tight when he eats and at times while he is eating he would stop eating because of the same pain. This has been going on chronically for the past three or four months and prior to admission his symptoms became worse and the day of admission increased in intensity and he became acutely ill.

Unlike kindergarten, where I distinctly remember the day I went home early from school due to illness, I have no memory of how or why I ended up in the hospital this time. Looking back at the doctor’s notes now, after all these years, I see that my situation was far more serious than my younger self could comprehend. The small town doctors in Neillsville gave up on me. Unable to help further, they loaded me into an ambulance and transported me to the much bigger hospital thirty miles away in Marshfield.

I was assigned to a Japanese-American doctor named Dr. Toyama. Years later, as an adult who had spent years living in Japan, I went back to Marshfield and found him again. I learned he was an issei—his parents had come to the US before he was born, and he grew up here (I don’t remember where exactly). Somehow he ended up living in the middle of Wisconsin and had spent his entire career there. He didn’t remember me very well – he claims he did, but with so many thousands of patients over the years it’s hard to tell exactly – but when I was a suffering eight year old, he was the center of my existence.

Upon arrival at Marshfield, Dr. Toyoma wrote in his notes about me:

He was doubled up in fetal position…the abdomen was flat, colostomy on the left side which was not yet matured…bowel sounds were absent…The child did appear exhausted.

Due to the pain, Dr. Toyama didn’t do long tube intubation and went straight to surgery, where

he was found to have a tight adhesive obstruction in several areas with collapsed bowel distal to the obstruction. The obstruction was in the mid small bowel. There was purulent non-foul fluid in the peritoneal cavity at the time of exploration, however, no perforation was noted. The colon appeared normal…cultures of the peritoneal fluid grew out pure culture of E-coli.

After conferring with the Neillsville doctors and my parents, Dr. Toyama decided that my original surgery hadn’t addressed the real problem, which was a sigmoid volvulus, an intestine that was predisposed to become wrapped around itself and become blocked. I had been sick for quite a while and there was a significant danger I had already sustained permanent damage, he feared, so I would require a series of surgeries to uncover the underlying problem and find a permanent solution.

Meanwhile, my current situation was extremely serious, he warned. I was so weak that there was already a good chance I wouldn’t survive. My brother and sister were called to the hospital – normally young children weren’t allowed inside the patient area – and were told, gently, that this might be the last time they see me.

I knew I was not well, but at the same time I also knew that I was very special: a constant stream of friends, relatives, and neighbors came to my bedside bringing all manner of presents. I was the center of attention! If anyone told me there was a chance I’d never leave the hospital, I don’t remember it, because I certainly didn’t feel like my life might soon be ending.

In fact, among other memories of that time, I remember thinking how wonderful it would be to fly in an airplane, maybe even become an airline pilot. I don’t think I was particularly worried one way or another about the future.

Marshfield was a great, modern hospital, with its own pediatric ward, full of other children, extra-friendly nurses and even special activities and visitors. Famous visitors who passed through town would often stop to see the hospital, and of course the pediatric ward was a must-see for them. One day the famous basketball performance team, Harlem Globetrotters, came in to my bedside and signed autographs for me. Lying in bed with an IV, tubes coming out of my nose, and with my weak, skinny arms, I must have been a pathetic sight, but I never remember any sense of concern around me. To me, it was all a place of wonder and nonstop attention.

There was one exception to my sense of calm. Since Neillsville was about thirty miles away, my parents – usually my mother – had to drive quite a distance to see me. Since she was responsible for my siblings as well, who were in school but still needed to be fed and cared for, she could be with me only during the day. The evenings after she left, and especially the mornings before she arrived were difficult and lonely.

My religion was a big influence on everything I did, so naturally I saw my hospitalization in the context of God and His purpose for my still short life. I had been taught that only a tiny few people had a true understanding of God’s plan for humanity, and that even among those of us who believed, we still fell short of what God wanted. And a sin is a sin; even one tiny, seemingly insignificant breach of God’s rules could keep you out of heaven just as certainly as the most dastardly bank robbery or murder. I knew that I sinned too – sometimes the worst sins of all are those that you do subconsciously, non-deliberately, in a moment of forgetfulness, and I had plenty of those.

Some sins are passive – what I would later learn to call “sins of omission”—when we know that we should do something but we don’t. These are among the most annoying sins because they result from laziness, or lack of willpower, and sometimes from simple shyness. For example, I knew that my fellow hospital patients were mostly unbelievers, and that I owed it to them to share my knowledge of the saving grace of Jesus Christ. By not sharing – by keeping silent when I knew that they could benefit from this message – wasn’t I falling into a terrible trap of the Devil? Wasn’t that a sin?

I knew the importance of keeping up my faith with regular prayer and Bible reading. Sometimes I forgot, or was too lazy or distracted. Wasn’t that too a breach of God’s will – a sin?

Although you’d think that an eight-year-old, weak with sickness, tired and injected with medications, would not have cause to think much of these things, in fact it was at the center of my mind. I knew that God loved me, and that it was only through prayer and diligently following His will that I had survived this sickness at all, but I also knew he was testing me for some greater purpose. Would I pass the test?

One morning, after a particularly difficult night of anxiety over this, I woke up thinking I knew the answer: clearly I had failed the test. I was convinced that this meant I would not be going to heaven at all, and with the imminent Rapture an ever-present possibility, I suddenly had a strong premonition that last night had been the moment when Christ returned to earth, and I was left behind.

I began to cry. A nurse soon noticed this and immediately tried to comfort me.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, holding my hand with a voice of sincere concern.

“I’m afraid,” I said, hesitating. Should I tell her my real fear – that the Rapture had happened last night and that I had missed it? If this were true, then it meant my nurse had missed it as well. Was this really the news that I wanted to break to her at this moment? First I’d need to explain all those other details of the Gospel, and she’d want to ask questions, perhaps challenge me with doubts. This whole explanation could take a long time, and at this moment I was just feeling sad that I wouldn’t see my mother again.

I decided to skip the long explanation and just cut to the point.

“I’m afraid,” I said, continuing, “that my mother won’t be coming back.”

As an adult looking back on this, I can imagine the reaction this produced in the nurse, who no doubt wondered what sort of family life could cause a little boy to doubt that his mother would visit him in the hospital. She was calm about it, though, listening to me and offering her reassurances that my mother would be there the same time she always was.

She was right: my mother walked into the room, to my immediate relief. The nurse explained that I had been especially anxious that morning, worried that my mother wouldn’t return, that this was a normal type of separation anxiety, not to be concerned, etc. That was it.

But I wonder if this had happened today, maybe she would have been required to note my behavior somewhere, perhaps a side report to a doctor or a social worker to be on the lookout for signs of family abuse or some other tragedy.

The burden of caring for me was so time-consuming that around this time my brother and sister were often dropped at the farm of our Pulokas Grandparents. I was too sick to know much about the time they spent there, but I know they enjoyed it. Partly of course it was because their grandmother spoiled them – delicious food and plenty of toys. Life on a farm can be especially fun for little kids. Gary enjoyed looking at the farm equipment – Grandpa even let him drive the tractor. They played in the hay mow of the barn, rearranging stacks of hay to make pretend forts. And of course there were animals: dogs, cats, rabbits and cows. Gary was old enough that occasionally Grandma would let him try milking, though despite Grandma’s patience he showed too little interest to be of much help.

There would be plenty of other visits to Grandma’s house when I came out of the hospital, but I know Gary and Connie kept special memories of that summer’s lengthy visit, when the two of them developed their first tastes of independence away from parents.

2.6 Gungors

The Neillsville of my first memories may have been rural, but it was not completely removed from “The Sixties” of the rest of America. One of my first glimpses came in art class, when the teacher let the girls bring record albums to play while we worked: popular songs of the day, like Leaving on a Jet Plane, or Do You Know the Way to San Jose, repeated over and over.

My school held bomb drills, last vestiges I guess of the 50s and 60s fear of nuclear war, where once or twice a school year we learned to duck under our desks for protection.

We had hippies, Hells Angels, and draft evaders just like the big cities. One day, while browsing a copy of US News and World Report, I came upon some photos of the Black Panthers, and my mother warned me to immediately report to her if I ever saw anyone like that in real life.

One sunny morning I woke up to find one of our downstairs windows shattered. Dad had run outside to catch the two teenage boys responsible. He apprehended them and was arranging to settle the matter with their parents, a doctor and his wife. Although they lived only a block away, that was the first time I heard their name: Gungor.

Dad had been working at the high school as a substitute teacher, and the two were in his class. Somehow the teenagers learned that Dad’s real occupation was a small-town preacher, and this was apparently funny enough to them that they decided to vandalize our house. I don’t know the full story, but if their intent was to intimidate my father somehow, their plans backfired.

This was not my father’s only close call. While setting up the church, he reached out to many people and groups on the margins: alcoholics, deadbeat dads, single moms and their unruly children. He even spoke to members of the nearby Winnebago Indian tribe, including one very large and mean-looking man named Rudy, who arrived at our doorstep once very late at night insisting that he needed to talk about God, alone, in a place far away.

Dad greeted all of these rough people with the same missionary zeal that led him to Neillsville in the first place, but his farm-raised instincts kept him well-grounded in the ways that people could be evil, so if Rudy started with any ill intents, they evaporated by the time Dad finished talking with him and Rudy became a regular church goer.

So it was with the Gungor boys, who quickly became enthusiastic members of our church, forming our local version of the “Jesus People”, a Hippie-inspired movement that spread with the Sixties, substituting Christianity for drugs but keeping the same dress code (long hair, blue jeans, bandanas) and focus on love and peace. The two boys, Ed and Mark, were also musically inclined and they formed a Christian rock band, drawing even more young people to our church.

One of them was their little brother, who was introduced to me in the basement of our church one Sunday as Jimbo, the precocious doctor’s son, who soon became my best friend.

Jimbo was a year younger than I was, but had skipped first grade and was a third grader like me. He was the pride of his mother, Lily, who knew he was destined for greatness and spared no expense to ensure he had the finest of everything. It was a treat to visit his house, which seemed overflowing with the latest toys of course, but also with books and innumerable puzzles and games. We soon discovered a mutual interest in Chess, Stratego, and many other board games of strategy that kept us busy every weekend.

Jimbo had a younger sister, Lisa, who was Connie’s age, and they became such close friends that they nicknamed each other “sissy”. Gary joined us too, and there probably wasn’t a Saturday where we all didn’t play together. In the winter, we could go to the Gungor’s large basement with its musty shag carpeting and endless games of the board game Life.

The Gungors had one important possession we didn’t have: a TV, a full-size color model that seemed to be always turned on. To us Spragues, this was both a treat and a mystery: we had no television at our house, so anything we saw was new. But in those days before home recording and cable TV, the viewing options were limited on weekend afternoons, so we watched less than you might think. Still, Jimbo watched enough that he was able to introduce us to TV-inspired real-life games, where we would imitate the premise of a show, taking on the roles of one of the characters, pretending to live in that world. Our favorite was Star Trek, which I had only been able to watch in brief glimpses, but with Jimbo we played incessantly. He liked to be Captain Kirk, Gary was Scottie – the resourceful fix-it man, and I of course was Spock, the unwaveringly logical, science-oriented, and endowed with special powers that let me do mind melds and Vulcan death grips.

It was also at the Gungor house that occasionally I was allowed a peek into his father’s study: a small room that was positively crammed with books and magazines. Dr. Gungor was a Bulgarian-born Turk who had lived under the Nazi occupation as a boy, became a medical doctor, and immigrated to the U.S. in the 1950s. It was while practicing in New York City that he met Lily, a lively Puerto Rican woman who became his wife. The rumor was that Lily had been a single mother with three young boys and she met Dr. Gungor while bringing them to his clinic.

I have no idea how such an unlikely family ended up in Neillsville. When I met them, the three oldest boys were followed by an oldest sister, Leyla, then Jimbo, and the youngest girl Lisa. It was a big family in the middle of Wisconsin farming country. A doctor’s income in Neillsville made them among the wealthiest families, and Lily’s gregarious personality meant they were among the most social families too, seemingly connected to everyone.

The Gungors, besides being close friends, also became for me an aspiration, of another world that could be realized through education and money. And their world was highly approachable: through my friendship with Jimbo I realized that money had great usefulness but it didn’t determine happiness or success.

2.7 The Pack

Though it’s true that people in a small town are naturally open and friendly to one another, that does nothing to diminish the human instinct to separate into smug cliques and, beginning in middle school, this segregation began in earnest.

There were early hints even in elementary school, like the time walking home with my brother in second grade, when the Larsen boys appeared out of nowhere and threw our art projects into O’Neill Creek. The projects weren’t that important, we told ourselves, and those kids were way bigger than we were, so we chose to simply ignore that act of meanness.

By middle school, though, the Larsen boys – especially Mike Larsen, the oldest – were completely out of hand. Between classes, Mike was always surrounded by the biggest, toughest boys, all of whom seemed permanently on the lookout for weakness. It was as if they fed on it, like vampires in a never-ending search for blood.

They found their first blood in David O’Grady, a friendly, slightly portly boy who otherwise was normal in every way. He was in the same grade as my brother, who was a friend and regular lunchtime and recess companion. But David had one conspicuous weakness that was quickly and mercilessly exploited by the unforgiving mean boys.

David had arachnophobia, a fear of spiders that was impossible to ignore among boys looking for a target to prove their own strength, because as every boy knows, nothing is a better proof of strength than the weakness of another.

The rumor was that David had, as a very young boy, been attacked by spiders in an outhouse while using the facilities, and the experience had traumatized him so much that he was barely able to think about spiders without getting chilly reminders of the incident. His fear was total, completely irrational, enough that the mere mention – the mere threat of a mention – would send him into a clear defensive stance, his eyes widening, his lips pursed, his stance ready to flee. The other boys, seeing his, could not resist the easy kill, and soon David was surrounded by taunts.

During the Fall and Spring, when live spiders were abundant and easily snared by the farm boys, David was in especially big trouble, but even Winter brought little relief. Nothing gave greater pleasure to the meanest boys than to draw a picture of a spider on David’s notebook – watch him squirm! – or to threaten that one had been discovered and was now – here – in my hand waiting to be tossed right in his face.

David, sadly, was unable to hide his fear. The mere mention of the word, the slightest hint that the very concept of spider was about to be brought into the room, send him shivering with chills. There was no refuge. When he tried to hide in the library, the boys brought him magazines and books with pictures of spiders. It got to be so bad that he couldn’t go near the “S” section of the library, for fear that a heartless bully might be lying in wait ready to pounce with a book of gruesome photos.

My brother, being an erstwhile friend of David’s, soon became a target as well. Gary was not himself afraid of spiders, but there was guilt by association, and the meanest boys began to search for his weaknesses, as if it was their solemn duty, like inquisitors, to find every soft spot in the school body.

Being younger, though only by a year, threatened to push me into the negative association as well, and I began to see constant reminders of how close I was to becoming the class punching bag. The mean boys showed no mercy on David O’Grady, and now the boys in my own grade, seeing the fun, couldn’t help but notice the advantages to their own status by being able to prove that somebody else was weaker. It seemed to be just a matter of time before they came after me too.

Jimbo was worried. A city boy through and through, he was unable and uninterested in the physical activities that the bullies respected. The meanest boys always traveled together, “like a pack”, he said, and soon that’s the label we assigned them.

The Pack. They congregated during free moments at school, like wolves hunting for prey at breaks between classes, at lunch time, and after school. If you saw them together, you knew it was trouble, and I soon learned to avoid certain areas of the school, or – when that was impossible – to make sure to pass only when other, weaker boys could be sacrificed to ensure my safety.

Gary and I were obvious weaklings. Both of us, tall and skinny, Gary with his awkward glasses, our pants always too short. Today’s school administrators, ever-vigilant against bullying, would have intervened to protect us. But we had no such help. There were no anti-bullying signs posted in the hallways, no hall monitors to watch for signs of the weak being exploited by the strong. We were on our own.

2.8 Religious School

The Neillsville public schools had for a generation been consolidated into a single building at the top of a hill on the eastern edge of town. I entered kindergarten on one side of that building and graduated high school on the other side. In between was a middle school that, in the mid 1970s needed major construction, a years-long project that required all sixth graders to bus daily to an old one-room schoolhouse outside of town, the only place large enough to hold the classes. My brother attended there for his sixth grade, and I would have gone there too, but about that time a new school opened in town: the pastor of the Bible Baptist Church began accepting students for a religious-oriented school for kids from kindergarten to high school somehow it was decided that I would attend too, for a year. Jimbo’s parents decided to send him as well, so the two of us joined about 20 or 30 kids each day in the pastor’s house, where small divided desks had been set up for our school.

The curriculum was from a national organization called Accelerated Christian Education that produced a series of go-at-your-own-pace workbooks on all subjects relevant to a primary school education. The process was simple: you take a short test to determine your initial classroom level, and you work your way through various assignments and quizzes in a workbook until you could prove through passing another test that you know the material. For me, it was a natural and easy way to learn and I breezed through much more than one year’s worth of material in the time I was there.

The curriculum’s initials, ACE, also stood for a series of “privileges” you could earn weekly for various academic-related tasks. The “A” privilege was easiest to achieve, and it allowed you to have regular recesses in exchange for completing a certain amount of work on time each week. “C” gave you additional recess time and it was flexible: you didn’t have to take your breaks with everyone else. In return, you were expected to do all the work required for “A”, plus extra, and there were some other tasks, like completing a book report. But I worked hard to achieve the hardest, “E” privilege, which gave unlimited recess time. You earn it with all the “C” requirements plus a class presentation and some Bible memorization. Although I started the year striving for “C” privileges, matching Jimbo, I soon realized that “E” wasn’t that much harder, and soon I was achieving “E” every week, greatly increasing my free time.

Attending the school allowed me to became good friends with many of the students, most of whom were hard-core Bible Baptists. One peculiar characteristic of religion is that often the biggest animosities are reserved for those who are more similar in doctrine than those who disbelieve altogether. So it is that Southern Baptists disagree more vehemently with Bible Baptists – often to the point of veering into personal attacks – than they do with, say, Catholics, Mormons, or even atheists. To a Bible Baptist, an atheist can be excused perhaps for simply misunderstanding the message of Christianity; but a Southern Baptist has no excuse. When the two denominations disagree – as they often do – about the meaning of a single word in a Bible verse, neither side is guilty of a misunderstanding. The only way such a disagreement could happen is through willful, perhaps even malevolent blindness.

To fundamentalist Christians, there is no greater apostasy than to break with the True Faith on the matters of theological urgency that separated our churches, and the year I spent with the Baptists was for me marked with great memories of theological debates, both with other students and with the pastor.

David Webster fit all the stereotypes of a thundering Christian fundamentalist: crew cut hair, always dressed in white shirt and tie, deeply and sincerely committed to his faith. I found him stern, but fair, and nobody could ever accuse him of hypocrisy: I know he sincerely believed in everything he taught, and he lived his life according to the principles he expected from us.

A fierce anti-communist and sincere follower of the John Birch society, he saw the hand of Satan in everything, and believed America was great only because of its Judeo-Christian principles, a bedrock that had greatly and perhaps irreversibly eroded by the time he met us. Rock ’n roll music, everyone in Hollywood, the international banking system, much of the scientific establishment, and many more powerful institutions were in open conspiracy against us, and we would prevail only by holding our Christianity tightly.

Our discussions at recess and lunch grew into deep theological, philosophical, and often scientific debates, and I thrived. He tried to convince me that my father’s church was victim of a terrible Satan-inspired lie that hinged on some subtle Biblical wording. Similarly, he taught me how science was polluted with demonic lies about the nature of God’s creation; Evolution of course was the worst offender of all, insidious because from a purely scientific standpoint it made a mockery of the scientific method. How could anyone be fooled by such obvious falsehood?

I learned so much from him that year, and from my fellow students, as we debated these great issues. For the first time I was forced to confront how my father’s religious beliefs were distinct from other Christians, but I was able to do it in a friendly environment of people who treated the Scriptures as sincerely as he did – the only difference being that they had found an alternative interpretation. Although I didn’t get to debate Evolution in the same way – we were on the same side on that issue – I learned to respect the skill of delving into facts, always looking for holes in my arguments, to be prepared for a debate with eternal and life-or-death consequences.

Technically, it was the village of Elk Mound, a 15-minute drive from the college – now University of Wisconsin Eau Claire – where my parents met↩︎

Who, I believe is the author of this history of our church for the Wisconsin Historical Society↩︎

Tragically, Tommy’s father died in drowning accident a few years later, and Tommy moved away when his mother remarried a few years after that↩︎

Interestingly, one of my children was born with and quickly got over a similar condition, so it may be hereditary. ↩︎